Upon which fundamental assumption is this divide based? What does this split create?

A REVIEW:

Before I address those questions, I want to take you into a quick review of Greek oratory, and particularly into a review of how syllogisms/enthymemes work. Why? Because this chart is fundamentally enthymematic, and that’s a crucial observation for understanding its weakness.

An enthymeme is a syllogism with a missing part--an argument that relies upon an assumption from the audience.

For example, a full syllogism would be:

MAJOR PREMISE: All humans are mortal.

MINOR PREMISE: Socrates is human.

CONCLUSION: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

The enthymematic version of this same premise would be truncated to:

Socrates is mortal because he is human.

In the enthymematic version of the syllogism, the major premise, “All humans are mortal,” has been assumed.

Whenever we find an enthymeme, it’s important to go back and look clearly at the part that has been removed because simply naming the missing premise often reveals assumptions that we would never accept if they were stated more directly.

So, looking back at the outline from the Blue Letter Bible, let’s create a syllogism from the enthymeme which drives this information.

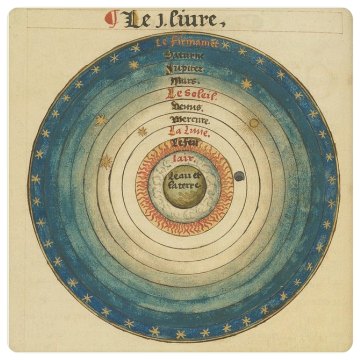

MAJOR PREMISE: Only two methods of interpretation are possible, empirical science and hermeneutical interpretation.

MINOR PREMISE: Interpreting the Creation narrative is dependent upon one of those two methods.

CONCLUSION: Therefore, interpreting the Creation narrative must rely upon either empirical science or on hermeneutical interpretation.

The Blue Letter Bible leaves out (but implies) the major premise: "Only two methods of interpretation are possible, empirical science and hermeneutical interpretation."

Is this implication legitimate?

A LITTLE BACKGROUND ON HERMENEUTICS/EXEGESIS

Without going into too much detail, the term hermeneutics generally refers to methods of interpreting Scripture--and hermeneutics is often dependent upon exegesis, a text-oriented exploration of the actual words of the Bible.

I am actually an exegesis junkie for several reasons, primarily because I trust the Word of God deeply; but secondarily, as a literary critic, I know how important a text-oriented mode of interpretation is. In the discipline of literature, we often refer to a text-oriented method of interpretation as Formalism (or New Criticism, or Textual Criticism). These schools of analysis argue that the text itself should be used as the primary means for finding meaning.

In the realm of theology, exegesis applies trust in the words of the ancient text—a posture which stands against more eisegetical approaches to Scripture that place less trust in the Word of God and more in human instinct or bias.

As I look at the Blue Letter Bible outline, I think it's understandable that the divide presented here has occurred. At present, conservative Christians feel pressure from two primary groups: (1) secularists who trust human reason, and (2) liberal Christians who elevate human instinct above God's authority. Given these choices, Conservatives have chosen to stand in firm allegiance to the Word of God, a stance I find admirable.

What we may have missed, however, is that a Greek, humanistic assumption also undergirds our counter stance: an assumption that human beings can access the true meaning of Scripture by rationalism alone.

I’m wary to address this assumption because unpacking it can turn into a bit of a Pandora’s box. Challenging trust in reason often leaves a vacuum, which leads to a trajectory of bizarre, ever-shifting, touchy-feely interpretations of Scripture. At some level, Christian theologians have a very practical need to believe that God is logical and that he has presented us with a book that can be unpacked by strictly rational means.

In general, I agree that God gave us reason, and he expects us to use it. (Why would I be writing a post like this if I didn't?) I also agree that the Bible is our ultimate guide for what is true. Yet God also leaves some tension here, and I think he does that intentionally. He's left mysteries and paradoxes in His Word alongside what is open and clear. Why? Probably because the very first sin of humans was an attempt to be Godlike without God. Trust in the ability of our own minds was our first idol, and we default back to this impulse every day of our lives.

To help protect us from this impulse, God gave us a complex Scripture that can't be reduced to a flow chart. In the story of Christ chiding people who believed that searching the Scriptures could be done by reason alone, he shows us that spiritual knowledge can't be obtained fully apart from dependent fellowship with him.

“You search the Scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life; and it is they that bear witness about me, yet you refuse to come to me that you may have life.” (John 5:39-40)

Over and again in the Word, we see evidence that pursuing religious activity apart from union with God leads to destruction. God uses rationalism, but he also limits it. Our Lord has created a faith that is not simply dependent upon the workings of the mind, but even more so, upon the posture of the soul.

So even though the outline provided by the Blue Letter Bible serves some good purposes, it fails to acknowledge the complexity of a truly Christian epistemology. We cannot know the way without actively knowing The Way.

AWARENESS OF OUR BIASES

While the Western church has been quick to attack empirical science, we regularly fail to see how much our own methodologies have been influenced by secular humanistic philosophies. In fact, in some ways, the simple bifurcation presented by the Blue Letter Bible reveals the prime epistemological error of the Western Christian church.

This outline claims that humans have two options:

(1) knowledge obtained by empirical science.

(2) knowledge obtained by hermeneutics which deals with the science of interpreting scripture.

Category 1 can be traced pretty easily back to David Hume, the father of empiricism (trust in the scientific method). But Category 2 can also be traced back through secular Western philosophy. In fact, Category 2 agrees with Plato and Descartes--that the prime essence of human beings is rational.

The Bible certainly affirms that part of the human nature involves the rational mind; however, even passages such as Romans 12:2 ("Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind") tend to fall in the larger context of what immediately precedes it: "present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God."

The human mind is woven inside of a larger, affective faith in the Scriptures. We don't just think truth, we swim it out in the activity of our belief. This is why Jesus embedded the work of the mind inside of the larger work of love: "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself.” (Luke 10:27)

Christ spoke this radical statement about 350 years after Plato's Divided Line theory had been created, and he spoke it inside of a Roman-dominated culture that was pregnant with Greek values. In the very face of all secular understanding of the essence of the human, Jesus is arguing that being human involves more than just thinking, we are creatures of being and doing. What we love and what we chase is a diagnostic.

For the most part, modern Christians have lost this connection. In general, we assume that what we think equals what we believe.

THE DOMINOES FALL

Every idea has a trajectory, and the trajectory of idolizing Christian rationalism has grave consequences. When Christianity becomes a purely rationalistic exercise, fulfilling the Great Commission shifts to dependence upon human arguments. We aren't simply Paul in Athens, using rationalism as a tool under the guidance and power of the Holy Spirit--we transform into flesh-powered, independent warriors, reduced to only the power of our own minds, attempting to fight fire with fire. We think we are serving God, but in truth, we are ignoring many warnings given to us in the New Testament--warnings urging us not to attempt to complete the works of God in the power of the flesh (Galatians 3:3).

Evaluating language used by certain Young Earth Creationists can provide evidence of this idolatry. These leaders threaten us openly, telling us that losing the battle of evolution will mean losing the great culture war of our faith. They ask us to forget what the Bible says about the gates of hell never prevailing against the church--we are told (and shown) that arguments alone will protect us from the aggression of the non-believing world. Nervous believers have embraced this fear wholeheartedly, rallying behind teachers who promise to protect our beliefs from the forces of atheism.

This entire approach is deeply secular. It's fear-driven, faithless, and false.

WHY IT’S UNNERVING TO EVEN TALK ABOUT THIS

Yet anyone who attempts to unpack this matter in our part of the country is likely to be faced with rash assumptions that "you are one of those 'librul'-old-earth creationists." In fact, just a few weeks ago, I overheard some silly gossip about my husband that was spread in our community--a dismissive claim that he didn't believe in a literal Genesis.

That comment made me laugh because I have never seen anyone hold the Bible in as high regard as my husband. It also made me sad because here was more evidence that vulnerable and uneducated people have been pumped full of pride and haughtiness without solid facts.

In seminars and debates, limited information has been packaged into drive-through Creationist meals. Men and women swallow the goods then walk out of those experiences with a saunter, often feeling far more confident than they should. They bloviate in the spirit of our age, quickly dividing the world into blacks and whites.

I wonder sometimes what these folks would do if they could look beyond Happy Meal theology—how would they process the God about whom John Donne wrote:

“ETERNAL God—for whom who ever dare

Seek new expressions, do the circle square,

And thrust into straight corners of poor wit

Thee, who art cornerless and infinite—

Could they handle reality that is more nuanced than the explanations they have been given? In fact, even St. Augustine (354-430 AD) taught that the Genesis narrative was written to suit the understanding of the people of the time, suggesting that creation occurred in a single moment instead of over six literal days. He wrote:

“Perhaps we ought not to think of these creatures at the moment they were produced as subject to the processes of nature which we now observe in them, but rather as under the wonderful and unutterable power of the Wisdom of God, which reaches from end to end mightily and governs all graciously. For this power of Divine Wisdom does not reach by stages or arrive by steps. It was just as easy, then, for God to create everything as it is for Wisdom to exercise this mighty power. For through Wisdom all things were made, and the motion we now see in creatures, measured by the lapse of time, as each one fulfills its proper function, comes to creatures from those causal reasons implanted in them, which God scattered as seeds at the moment of creation when He spoke and they were made, He commanded and they were created. Creation, therefore, did not take place slowly in order that a slow development might be implanted in those things that are slow by nature; nor were the ages established at plodding pace at which they now pass. Time brings about the development of these creatures according to the laws of their numbers, but there was no passage of time when they received these laws at creation.”

Likewise, St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274 AD) wrote:

“On the day on which God created the heaven and the earth, He created also every plant of the field, not, indeed, actually, but “before it sprung up in the earth,” that is, potentially.…All things were not distinguished and adorned together, not from a want of power on God’s part, as requiring time in which to work, but that due order might be observed in the instituting of the world.”

The church fathers allowed for such complexity. They didn't tie up heavy burdens on the backs of their disciples--they understood ancient literature, genre, and language at a level that most modern believers cannot and allowed the Bible to be what it is. How grievous that we moderns rarely have the humility to admit that our cultural fears and our lack of knowledge have driven us to demand very particular results from Bible... fears and ignorance that lead us to commit some of the same interpretational errors that we accuse liberals of committing. We regurgitate distortions of the text that we have been given in seminars, trusting a secularized machine of Christianity that drives us into culture wars and away from resigned communion with the Holy Spirit.

THE BOTTOM LINE FOR ME:

Even as I write, I can feel a circle of wolves gathering, asking for my bottom line. Do I believe in six days of creation? Well, how about I take that request and raise you one. Why not ask me if I could believe in Augustine’s "instant of creation?” Might I dare to believe something so very radical as this?

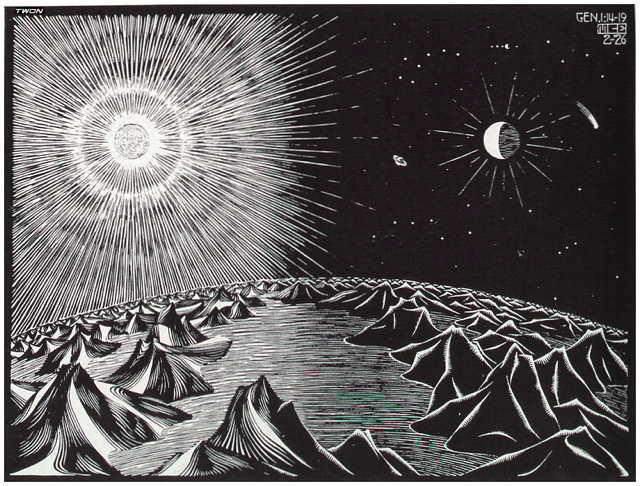

Gladly and without flinching. Neither a one-day nor a six-day creation model would be a stretch for the God I know, for he is not confined by time. Time is a dimension, after all (like length, width, and depth), and God transcends dimensionality.

However, I will also stand firm on this point: militarizing six-day-creation in an attempt to gain cultural power is not God’s plan for the book of Genesis. In fact, I think that a manipulative application of scriptural literalism is one of the most secular activities Christians can embrace. To adopt such a posture is not an act of faith; it’s trust in the Greek dialectic. It’s trust in the strength of humanity to accomplish the purposes of God. While I am eager to believe any wild miracle God sets before me, I will not link arms with Christianized humanism, nor will I give the slightest allegiance to such an endeavor.

ANOTHER WAY TO APPROACH THE BOOK OF GENESIS

A few days ago, a friend of mine posted a longish story in a Facebook status, and to tease her, I commented on a little detail she mentioned but that wasn’t central to her main post.

“That’s not the point!” she responded, and I laughed, because I knew it wasn’t. I was distracting instead of reinforcing what she was trying to say.

This distraction was (kind of) funny in the context of a casual dialogue, but there's little to laugh about when diverting the book of Genesis. When we major on the minors, we commit idolatry, worshipping rationalism, and worshipping our own ability to think our way through our present culture wars. We WANT this book to somehow fit into the categories that we create for it because we are scared, angry, and insecure. Our hearts are full of the Scopes Monkey Trial, and the nervous desire for Christian liberties. We tremble before every threat we’ve ever heard about the ability of hell (or the ability of progressives) to knock down the church of Jesus Christ.

All this fear undermines our focus-- preventing us from coming to Scripture as recipients, ready to commune with a living God who will use his Living Word to convict and guide us. When we flatten a book like Genesis to fight our personal wars, we miss the greater good it can do when we kneel before it and receive what it has to offer.

A few paragraphs ago, I mentioned one literary critical method—Formalism. What I didn’t mention was that Formalism is best balanced by a second method of literary interpretation called “New Historicism.”

New Historicism understands that every text falls into a historical and social context; for example, without understanding the larger historical concepts of “the landed gentry” or “entailment,” a reader might miss a great deal of the meaning in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. So while the text itself is vital, a responsible and humble reader also does enough background work to accurately orient a work in time and place.

In light of this, why was Genesis written? Was it given to Israel to help them fight the Philistines--who just happened to be raging Darwinian evolutionists? Of course not. It was given to help Israel understand its origins--not simply its material origins--but perhaps even more so, its hamartiaology--the origins of mortal posture toward an immortal God.

From whence did humans come? From a first mother Eve who chose to be like God apart from obedience to and communion with God. From whence did humans come? From a first father Adam who chose to be passive, to hide, and to blame.

When we read Genesis and immediately say, “Those blasted evolutionists!” we fail to learn what Israel was supposed to learn from its words-- a recognition that we are still Eve, worshipping our own minds. We fail to learn that we are still Adam, deflecting responsibility and blame instead of owning our own weakness.

If we encounter this text and immediately move into societal attack instead of allowing it convict us as it convicted the original audience, we have largely missed the point of the whole narrative.

I will always be an advocate of exegesis because I see grave dangers in intuition-based, eisegetical approaches to Scripture. Yet there is also a way to approach hermeneutics in living faith— with a far deeper commitment than that afforded by the Cartesian/Platonic rationalism that runs rampant through evangelicalism at present.

Ultimate allegiance to the text is determined by embodied believers who sit in deep submission to the Word of God— lovers of God who let his truth saturate down to the heart, soul, strength and then the mind.

Disciples of Jesus are not just thinkers, but active swimmers in the vast ocean of a living God--men and women who are willing to use rationalism as God gives it, but who plant their deepest trust in the Living Lord who goes before us into the World. He has not given us a spirit of fear, but power and love to accompany our sound minds.

That indwelt life will always align with the Word of God--it will never become a progressive do-what-feels-good deconstruction of orthodoxy. It will also involve far more than simple intellectual assent.

In the book that C.S. Lewis considered his masterpiece, a protagonist named Orual is trapped in a primitive culture that worships a wild god called Ungit. Because Orual is an intellectual, she spends most of her life trusting a foreign Greek rationalist teacher, a father-figure who embodies a linear, syllogism-based approach to truth.

During most of the book, the worship of Ungit is presented as superstitious and foolish, and the reader happily sides with Orual’s prejudices against her. And yet, in the end, Lewis pulls the rug out from under our feet. The wild god of the mountain must be known by trust and not simply by reason, and those who were willing to chase love end up being wiser in the end than those who trusted their own minds.

I was stunned when I realized what Lewis was doing with this book. Of all people, Lewis had such a rare ability to reason and debate. He was one of the great apologists of the faith, and yet, here he was, advocating for embodied trust with the greatest work of his life.

In this book he writes: “Holy places are dark places. It is life and strength, not knowledge and words, that we get in them. Holy wisdom is not clear and thin like water, but thick and dark like blood.”

I agree. And I think this deep wisdom should carry us through the book of Genesis. We should approach this book on our knees-- not with arms akimbo, sauntering through our culture as we point our fingers out there at “those bad guys.”

Let’s sit under it, friends. Let’s wade into it with longing for the God who made all that exists. When the good text says, “The earth was without form and void, and darkness was over the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters,” let’s shiver with awe, allowing those words to raise the goosebumps on our arms, for it is an image which falls like “shining from shook foil.”

Let it make us small before a great God. Let it lead us to sit before him and ask, "What am I that You are mindful of me? And yet..."

Let’s not be distracted by lesser pursuits and allegiances, nor by battles already won by an omnipotent God, but whisper like the wisest women in Lewis’s best novel, “The sweetest thing in all my life has been the longing — to reach the Mountain, to find the place where all the beauty came from — my country, the place where I ought to have been born.”

“Do you think it all meant nothing, all the longing? The longing for home? For indeed it now feels not like going, but like going back.”